1976

09.06.2021

Jacopo Prisco, CNN • Updated 10th May 2021

Judgment of Paris: The tasting that changed wine forever

(CNN) — In a Parisian hotel 45 years ago, some of France's biggest wine experts came together for a blind tasting.

The finest French wines were up against upstarts from California. At the time, this didn't even seem like a fair contest - France made the world's best wines and Napa Valley was not yet on the map - so the result was believed to be obvious.

Instead, the greatest underdog tale in wine history was about to unfold. Californian wines scored big with the judges and won in both the red and white categories, beating legendary chateaux and domaines from Bordeaux and Burgundy.

The only journalist in attendance, George M. Taber of Time magazine, later wrote in his article that "the unthinkable happened," and in an allusion to Greek mythology called the event "The Judgment of Paris," and thus it would forever be known.

"It was a complete game changer," says Mark Andrew, a wine expert and co-founder of wine magazine Noble Rot, "and it catapulted California wine to the top of the fine wine conversation." Wine had gotten its watershed moment.

A trip to California

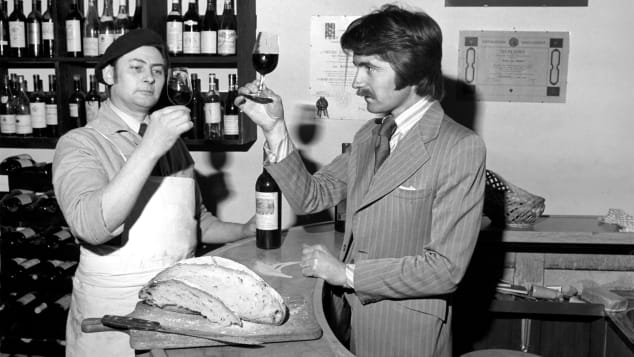

UK wine expert Steven Spurrier, right, came up with idea for a blind tasting contest.

The tasting was the brainchild of British wine merchant Steven Spurrier, who passed away in March 2021 aged 79. "He was a legend," says Andrew, who had known Spurrier for 15 years. "He was an open-minded guy who really knew wine, based on its quality and its intrinsic value rather than reputation."

In the early 1970s, Spurrier owned a wine shop in Paris and a wine school right next to it, called L'Academie du Vin. Both were aimed primarily at non-French speakers and were located on the Right Bank of the Seine river, where most of the foreign banks and firms were.

Spurrier liked to showcase wines from countries other than France in the shop and at the school -- an act of true rebellion in Paris -- and thought of a tasting as a way to promote his business.

Patricia Gastaud-Gallagher, an American associate of Spurrier, visited California wineries in 1975 and was impressed with the rising quality of their offerings. She suggested to look into such wines for the tasting and have it take place on the bicentennial of the 1776 American War of Independence. She also encouraged Spurrier to visit California himself, to pick a few worthy candidates.

And so, in early May 1976, Spurrier and his wife Bella took off for San Francisco for a wine tour. The tour was arranged by Napa resident and connoisseur Joanne DePuy, who showed the Spurriers around. "Steven wanted to go to the smaller, boutique wineries," she tells CNN. "He had a very good palate and he bought the wines he liked, at full price."

Bottles on a plane

The American wines were brought across with a group of 30 Californian winemakers.

DePuy played a crucial role in setting up the tasting, because Spurrier realized that carrying two dozen bottles of wine with him on a plane would be difficult, and there was a risk of having them held at customs. Instead, he asked DePuy to take the wine to Paris, since she had a tour of French vineyards lined up for mid-May, with 30 Californian winemakers traveling with her. The bottles could be transported as personal allowance.

"One bottle broke," she remembers. "Steven arrived to meet me in his customary white suit. We were there waiting for my luggage, and for the cases of wine. I smelled it before I saw it -- one of the cases had red on the outside and I said, 'Oh, my.' But Steven was very kind. He said, 'That's all right, not a problem.' He had at least two bottles of each wine."

The tasting, now six months in the making, was scheduled for May 24, 1976 at the Intercontinental Hotel, not far from Spurrier's shop and school. The nine judges, all French, included Odette Khan, editor of a prestigious wine magazine, and Aubert de Villaine, the director of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, a Burgundy estate that makes some of the world's best, and most expensive, wines.

Spurrier had no intention to cause a stir or to humiliate his French judges. He wanted little more than to create recognition for Californian wines and generate publicity for his school. But he did come up with a way of making things more interesting: he picked the four best white wines from Burgundy and the four best red Bordeaux blends from his cellar to go against the American wines, and covered up all the labels.

"It was only pretty much at the last minute that Steven decided to change the testing from an open one to a blind one. Blind tastings are common now, but at the time, it was a very innovative way to compare and contrast wines," says Andrew.

Among the French wines Spurrier picked were Batard-Montrachet, Chateau Mouton-Rothschild and Chateau Haut-Brion -- the elite of fine wine. The Californian offerings, 12 in total, included Ridge Vineyards, Freemark Abbey, Spring Mountain, Stag's Leap Wine Cellars and Chateau Montelena -- all of which were largely unknown in Europe.

The journalist George M. Taber was given a card with the names of the wines that were being served, so he knew exactly what the judges were tasting. He soon realized things were getting interesting when one of the judges tasted a white wine and proclaimed, "This is definitely California. It has no nose," when he was really tasting the Batard-Montrachet, a Burgundy Chardonnay that is often categorized as one of the world's best white wines.

The unthinkable was indeed happening.

When Spurrier tallied the scores, it turned out that California had dominated the white wine category, with a 1973 Chardonnay from Chateau Montelena as the winner, and three American wines in the top five. In the red category, a 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon from Stag's Leap Wine Cellars came out on top, narrowly edging out a 1970 Chateau Mouton-Rothschild from Bordeaux.

It was a David versus Goliath outcome, with wines that were much cheaper and younger unexpectedly getting rated higher. The Chateau Montelena retailed at the time for about $6.50 per bottle, a small fraction of the cost of its French rivals; Stag's Leap had been founded just six years earlier, in 1970, whereas winemaking at Chateau Mouton-Rothschild had been going on for three centuries. Both winners hailed from Napa Valley, which would go on to become one of the world's premier wine regions.

The French judges were far from impressed with the results. Odette Khan unsuccessfully demanded her scorecard back, according to Taber, so that the world wouldn't know how she scored the wines, while Aubert de Villaine later described the event as "a kick in the rear for French wine."